If we make ‘rouge’ a verb, and wish ‘to rogue’ something away, this is not so much a matter of will and method, as a question of attitutde. There is a warning here: there is no integral relationship between Art on the one hand and works of art and artists on the other. Art has nothing to do with critics, agents, museums, collectors, the viewing public or the media. And once Art itself becomes an object of attention, it becomes a shoddy, vulgar copy of itself, which everyone is capable of possessing.

– Li Shan

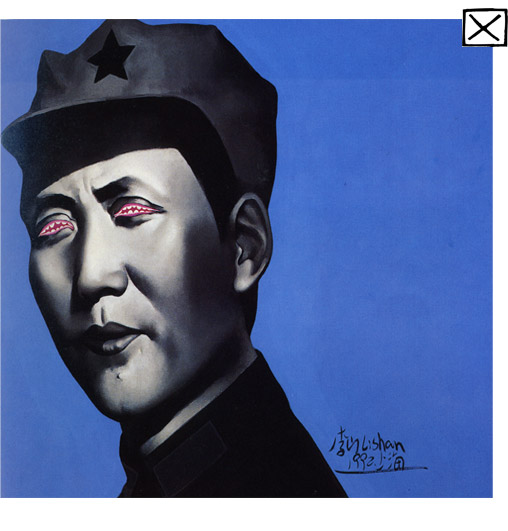

In Blue Mao, he manipulates Mao’s image by preserving parts of the basic black and white features and enhances the portrait with a graphic treatment (Hung). Mao’s head is juxtaposed with a blue plain monochrome background.

The representation of young Mao could be compared to the Educated Youth who were sent to the countryside for “reeducation.4” By utilizing the image of young Mao, Li could project his own memories of the time onto the painting. In order to cope with the painful memories of the Cultural Revolution, artists “tried with near desperation to rip away the memory of their youth from history and the discourse of history” (Smith). There is a certain level of self-identification within the work. The fantastical colors depicting Mao allow the implausibility of identifying with Mao plausible. The history of Mao becomes “fantastic and absurd” (Smith).

In Blue Mao, Mao wears the grey-blue Eighth Route army cap against a flat blue surface, common in many Mao portraits. The thin brows and cartoon droop of the eyes “suggest a pin-up idol” (Smith). Mao’s gaze hints to the all-seeing and all-knowing leader. Underneath the beauty of the image are undertones of hatred and China’s haunting history. The figure’s gaze follows the image outwards, suggesting that something has occurred beyond the bounds of the picture (Hung). A level of distrust exhumes from the image, creating a sense of uneasiness about the figure and about China’s past.

The series’ title Rogue refers to the consistent pink in the paintings. The colors employed by Li refer to folk art popular during the New Year. Both utilize flat pastel colors, but for different purposes. Folk art was painted in shades of pinks and blues for easy production and acceptance by the masses. Li employs the pastel shades to comment on the vulgarity of propaganda paintings against the epitome of high political status (Hung). The sharp yellow-colored star refers to the Communist Party and its overwhelming power during the Cultural Revolution.

Mao’s pink lips feminize his face and features. The overall work is injected with playful colors, and infused with “erotic sensuality that tweaks the corners of painted mouths … and fosters a cosseting intimacy on … the slant of the smooth-lidded eyes” (Hung). By questioning Mao’s sexuality, Li comments on the delicate balance between perversity and power. Sexuality becomes even more important when placed in the context of the PRC. During the rise of the PRC and the establishment of communes, women and men were given ‘equal’ rights. Women were given tasks commonly assigned to men. Propaganda posters de-feminized the female to such an extent that the only difference between the two sexes was the lightly flowered patterned blouse (Evans). Mao too, moved beyond a gender: “when you think of Mao you don’t think specifically of a man or a woman but a person with “Mao” characteristics” (Hung). And with the more explicit reference to sexual identity represented by the lotus flower, Blue Mao redefines Mao’s iconic image.